Ghana’s millennial generation wants a change to the status quo, and with 57 percent of the country’s population under the age of 25, it is time for leaders to take note. The new government hopes that strengthening the agriculture sector will help to create jobs and combat youth unemployment. However, the government may have to convince young Ghanaians that focusing on agriculture is the right solution, according to a national survey sponsored by the Center for International Private Enterprise (CIPE). The country’s economic landscape is changing, and with increasing connectivity and the rise of Accra as a regional hub, young people will not be content with their parents’ agricultural jobs. Instead, they want stable work that benefits from the promises of a transitioning economy.

In Ghana, the disconnect between opportunities presented by the government and the type of jobs that young people want poses a major obstacle to democracy and economic development. Education holds the promise of access to better jobs, and the government will be under pressure to deliver these jobs as more of the country’s youth reach working age. What constitutes a quality job for young Ghanaians? For now, the answer does not seem to lie in agricultural jobs. In order to respond to the needs of Ghanaian millennials and support economic growth and transition, it is an increasingly important question to ask.

Since taking office in early 2017, Ghanaian President Nana Akufo-Addo has launched five policy initiatives to support agriculture, education access, and job creation, and foster a business-friendly environment. Following Akufo-Addo’s election victory in December of 2016, CIPE and the Institute of Economic Affairs (IEA) in Ghana conducted a national survey of Ghanaians’ top policy priorities. VOTO Mobile administered the survey via cell phone in March 2017 to 1,641 people across Ghana’s 10 regions. The survey results, as interpreted by CIPE, indicate national support for reducing barriers to education, and a shift away from agriculture among younger Ghanaians.

Education is Top Priority Nationwide

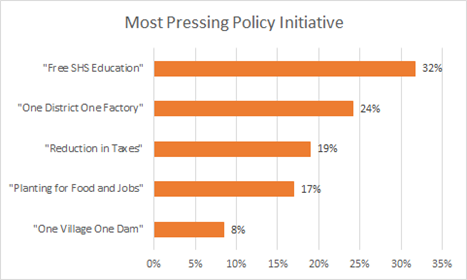

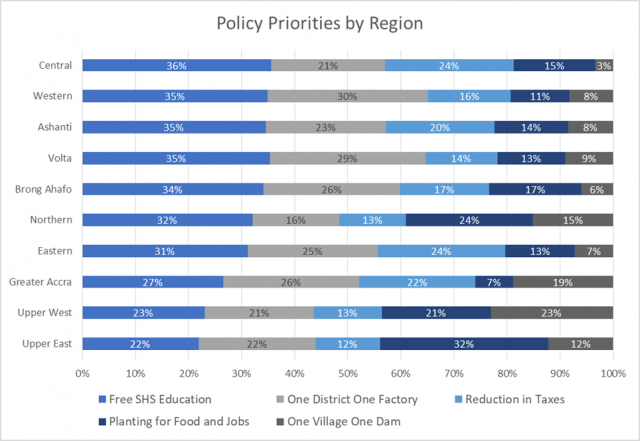

Improving access to education is a top priority for Ghanaians across most regions and age groups. In the survey, IEA asked Ghanaians which of the government’s new policies they considered a priority for implementation. Survey respondents in nine of 10 regions (32 percent of respondents nationwide) pointed to the “Free Senior High School Education” initiative as their preferred policy. It was the most supported policy across every age group with the exception of respondents between the ages of 26 and 35, who prioritized industrialization. The nationwide support for secondary education suggests that Ghanaians see education as essential to increasing economic opportunities for the next generation. Twenty-four percent of Ghanaians surveyed said the most important program is the “One District, One Factory” initiative to support youth employment through industrialization.

Currently, the cost of senior high school is a barrier to education in Ghana. The country’s net enrollment in primary education is 87 percent—higher than Sub-Saharan Africa’s average. However, Ghana’s public school enrollment drops to just 49 percent in senior high school, with a 46 percent completion rate. While public-school tuition is free, fees for admissions, library usage, sports, and room and board for students who live away from home weigh heavily on many families. For the current school year, first-year schooling fees range from $125 to $229 USD—a high price tag for a country where the median annual household income barely exceeded $2,000 in 2013.

While the previous administration instituted a “progressively free” education policy, which gradually reduced schooling fees over several years, the new free senior high school education promised by Akufo-Addo’s administration would eliminate fees entirely and provide free textbooks and meals for students. The government launched the policy for the current school year with an estimated price tag of about $234 million (USD). The government is working with partners to ensure that teachers and schools are able to absorb the anticipated increase in student enrollment without sacrificing the quality of public education, according to Akufo-Addo.

Reducing the cost of education is not the only barrier the government will need to address to help young Ghanaians stay in school. The survey results also reflect the trade-offs that many families must make between education and subsistence. This is especially true in Ghana’s poorest regions, where agriculture dominates the economy and support for the education initiative was lowest. In Upper East, one in three school-aged children is employed full time, predominantly in agriculture.

A Generational Divide Over Jobs

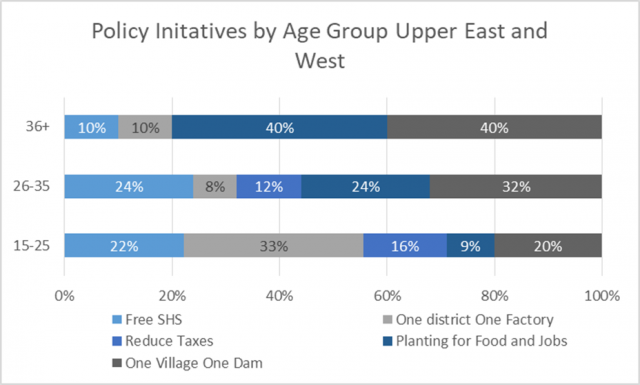

Young Ghanaians in the most rural regions do not see a future in agriculture, according to CIPE’s survey results. Support for agricultural initiatives (“Planting for Food and Jobs” and “One Village, One Dam“) is lowest among 15- to 25-year-olds in Upper East and Upper West. What is perhaps most striking is the divergence in support for agriculture among the three age groups. Eighty percent of respondents age 36 and older identified the two agriculture-related policies as their top priority. This compares to 56 percent of 26- to 35-year-olds and just 29 percent of 15- to 25-year-olds who prioritized agricultural initiatives. Conversely, more than three times as many 15- to 25-year-olds supported the industrialization policy than any other age group, suggesting that agricultural work is not desirable to young Ghanaians.

Despite minimal support for agriculture among young Ghanaians in Upper East and West, agriculture is a strategic sector for the government. Ghana is one of the leading cocoa producers in Africa, yet is still a net food importer of consumer-ready food products. The “Planting for Food and Jobs” initiative promises to support domestic crop production and improve domestic agri-processing with the goal of creating jobs and reducing migration to cities.

The value generated by industry and services—where young people see opportunities and want to work—is four times greater than agriculture, according to 2015 figures. The Ghanaian economy stands to gain from building domestic capacity to transform raw agricultural products. Nevertheless, in order to realize these gains, it is necessary to have a workforce that believes it will benefit from working in the sector. Agricultural jobs are physically demanding and are less stable than the average manufacturing job. Even outside of crop production, a bad year for agriculture usually means layoffs in agro-processing, subjecting the whole sector to the whim of Mother Nature. Advances in agricultural technology and connectivity in domestic supply chains may help mitigate these risks by smoothing uneven demand and reducing labor intensity. Nevertheless, for now, the promise of a “quality job” in agriculture remains a tough sell.

Click here to read more about how mobile surveys aid data collection.

Hanna Wetters is the Program Assistant for Africa at the Center for International Private Enterprise (CIPE).

Published Date: November 02, 2017