The following is part 2 of a 3 part series by Ryan Musser about Nigeria’s elections postponed to Saturday, February 23, 2019.

Read part 1 here.

As Nigeria heads to the polls on February 16, corruption remains an endemic issue in Africa’s largest economy, harming its public finances, deterring business investment, exasperating inequality, reducing the standard of living, and weakening the social contract between the government and its people.

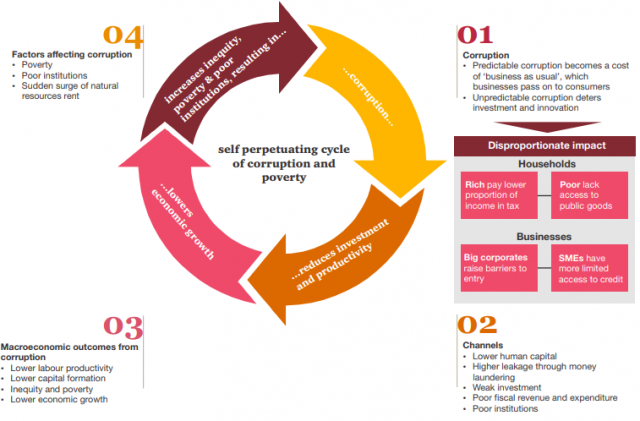

In a recent report on the impact of corruption on Nigeria’s economy, PricewaterhouseCoopers warned that corruption could cost Nigeria up to 37% of GDP by 2030, or around $1,000 per person, if not addressed immediately. The report found that corruption has a dynamic impact, which is felt the most by poorer households and smaller firms in Nigeria. Corruption has been described as an “existential threat” to Nigeria and “the single greatest obstacle preventing Nigeria from achieving its enormous potential.” Matthew Page, who developed a taxonomy of corruption in Nigeria, described the country as one of the world’s most complex corruption environments and has identified 500 distinct types of corruption that occur in the country.

Having campaigned in 2015 as an anti-corruption crusader, Buhari, nicknamed Mai Gaskiya or Mr. Honesty, is still seen by many to have impeccable personal integrity and still puts anti-corruption at the forefront of his agenda. “A policy program that does not have fighting corruption at its core is destined to fail,” Buhari proclaimed. “The battle against graft must be the base on which we secure the country, build our economy, provide decent infrastructure and educate the next generation.” But after four years of Buhari’s agenda, Nigeria still remains highly corrupt.

Indeed the administration maintains that it has made progress on its war on corruption. It has prosecuted some big fish, including two former governors. The administration has implemented some reforms, such as a single Treasury account, in which government oversees a single bank account for all revenue. It has introduced a biometric identification system in banks to trace clients and transfers of funds and established the Presidential Advisory Committee against Corruption. It claims it has recovered almost $550 million by removing ghost workers from the public payroll, a total of $370 million has been returned since the launch of a whistleblower policy, and $2.9 billion of embezzled assets have been returned

These are positive steps, but Buhari’s anti-corruption campaign has been selective, ineffective and has lost credibility. He has ostensibly targeted political enemies and looked the other way when his friends engage in corruption, such as the Kano governor Abdullahi Ganduje, who was secretly filmed receiving bribes and stuffing the money into his robes. Instead of prosecuting him, Buhari endorsed him. One of Buhari’s critics, Senator Shehu Sani of Kaduna Central, aptly described Buhari’s double standards: “When it comes to fighting corruption in the National Assembly and the Judiciary and in the larger Nigerian sectors, the president uses insecticide, but when it comes to fighting corruption within the presidency, they use deodorants.”

This disproportionate anti-corruption campaign has had political implications. Some political opponents being pursued for corruption charges have defected to Buhari’s APC precisely to escape investigation – and have been welcomed with open arms by the APC. These protected defections have exposed the hypocrisy of Buhari’s anti-corruption crusade. “Join APC and all your sins shall be forgiven,” declared quite boldly APC’s party chairman Adams Oshiomole.

Despite Buhari’s anti-corruption bravado, since 2014 Nigeria has maintained an average score of only 27 out of 100 in Transparency International’s (TI) Corruption Perception Index. TI points to a number of positive steps that the Buhari administration has taken, including the establishment of a presidential advisory committee against corruption, improving the anti-corruption legal and policy framework in areas like public procurement and asset declaration, and developing a national anti-corruption strategy. “However, these efforts have clearly not yielded the desired results. At least, not yet,” TI concluded. After four years of Buhari making fighting corruption his primary policy goal, Nigeria is still ranked 144/180 for perceived corruption.

In addition to the politically asymmetric quality of Buhari’s anti-corruption campaign, his reforms have not been deep enough. He has focused on symptoms – seizing looted funds and arresting corrupt figures – but has ignored the underlying structural causes of corruption. In an apt Nigerian metaphor, anti-corruption crusader Soji Apampa describes Nigeria’s corruption problem as “a broken pipeline with all of Nigeria’s resources flowing through it. Instead of fixing the hole, you bring a man with a whip” to deter people from stealing, he says. “We haven’t seen a government with an elaborate plan” to repair the pipeline, he says.

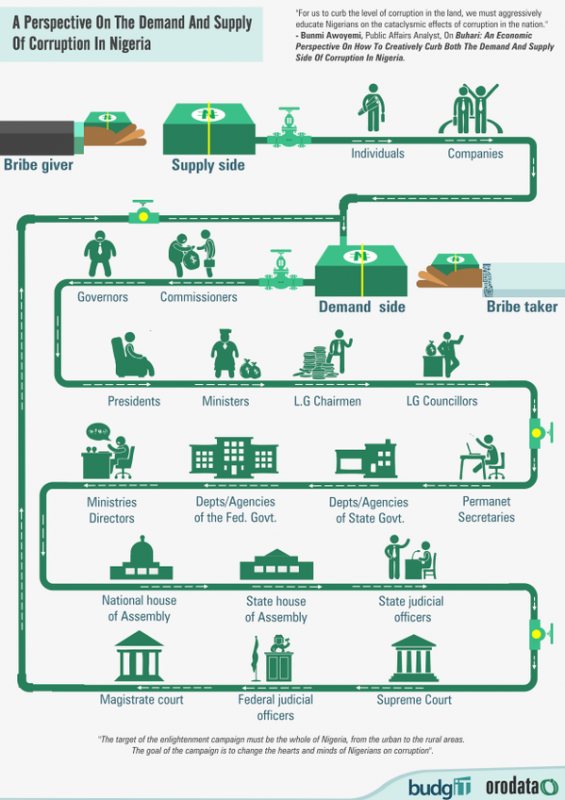

Buhari’s anti-corruption reforms are dependent on the support of the presidency to continue, leaving them weak, feeble, short-sighted, and prone to political exploitation, as we have seen. Anti-corruption reforms should be institutionalized and kept independent from presidential whims and desires. They also should be brought more to the state and local level. As Idayat Hassan, the director of the Centre for Democracy and Development, observes, Buhari’s anti-corruption crusade “has largely been targeted at the political center in Nigeria, meaning there has been relatively little impact at the state and local government levels.”

But while Buhari has disappointed, corruption is Atiku’s most serious flaw. Atiku is both a politician and a businessman, though he says he is a businessman first, not a politician. He made his fortune in the oil sector, where he co-founded Intels, an oilfield logistics firm, and grew it from a shipping container to a multi-national, multi-billion-dollar company. He now has a sprawling business empire in telecommunications, transport, real estate, agriculture, import/export, and healthcare. He represents success, but also embodies the questionable way that some Nigerian business owners have become successful.

In 2006, Atiku was accused of having diverted $125 million of public funds towards his business interests. A 2010 US Senate report entitled “Keeping Foreign Corruption Out of the United States” accused Atiku of money laundering, having transferred $40 million of “suspect funds” to the US. He was also embroiled in a corruption scandal that famously brought down US Congressman William Jefferson. Atiku was accused of demanding $500,000 in bribes to facilitate contracts to two American telecommunications firms, including one that Jefferson had a financial interest in. In a secretly recorded conversation, Jefferson stated that Atiku was promised the $500,000 for influencing the contract award. When the FBI raided Jefferson’s home, they found a freezer full of $90,000 that was supposedly to be paid to Atiku.

None of these accusations towards Atiku have been proven, and Atiku has denied them. Until a couple of weeks ago, Atiku had not set foot in the U.S. for 13 years. Opponents argued that he was barred from traveling to the U.S. because of these corruption charges. In the past, he said that he was not avoiding the U.S. but had been denied a visa. In January, he made a surprise trip to the U.S., putting to rest talking points about his inability to travel – but not his complicity in corruption. At any rate, Reuters reports that U.S. government officials said the travel ban was waived temporarily after a lobbying campaign was mounted among congressional lawmakers, arguing that the lead opposition figure should not be snubbed.

Atiku has not said much about corruption in Nigeria and his plan to fight it. Understandably, he has attempted to shift the discussion away from corruption and focus more on the economy. When he publicly unveiled his policy document, however, he did call for a coordinated national anti-corruption strategy that includes building strong anti-corruption institutions that cannot be manipulated by individuals, and establishing within the institutions a culture of increased transparency and accountability in a non-partisan manner. He has said he would increase the salaries of public officials to reduce what has been called “the corruption of need” and he has proposed an amnesty program that would allow citizens accused of graft to return funds without being prosecuted. Besides the amnesty program, these are good policies in theory, that get more to the root of corruption and institutionalize responses. But given Atiku’s personal track record, it remains highly questionable whether he will act on these proposals. It seems more likely that Nigerians will be choosing between an ineffective, hypocritical anti-corruption campaigner and an alleged, amoral kleptocrat.

But the political leader isn’t the only one who can fight corruption. Business can – and should – be part of the solution to corruption. CIPE believes business can play a crucial role in tackling corruption, no matter who is president. In Nigeria, we have worked with the local private sector on a number of projects to empower the business sector to combat corruption. Several years ago, CIPE partnered with the Lagos Chamber of Commerce (LCCI) to survey Nigerian businesses and identify the government regulatory agencies perceived as most corrupt. The study revealed that the Standards Organisation of Nigeria (SON) and the National Agency for Food and Drugs Administration Control (NAFDAC) were seen by local business to be most corrupt and the challenges and costs of dealing with these regulatory agencies were major factors stifling healthy growth of businesses across several sectors of the Nigerian economy. As part of a continental-wide anti-corruption project, CIPE is working with a local partner the Institute of Directors – Centre for Corporate Governance, to train and consult local Nigerian businesses in mitigating the risk of corruption by conducting a corruption risk assessment, setting up an effective anti-corruption compliance system, and strengthening business ethics and integrity. CIPE has also supported IoDCCG in collaborating with the CFA Society Nigeria to develop a corporate alliance to promote ethics and integrity in the Nigerian business community.

Tackling corruption in Nigeria requires a multi-pronged approach. Political leaders play a crucial role in this fight through their use of the bully-pulpit, their ability to create and enforce laws and regulations, and craft institutions. Civil society also has a role to play as a watchdog, demanding transparency and accountability. But the business community should also be active in the fight against corruption. The private sector is the supplier of corruption in the system, whether it is out of a willingness or a sense of survival. Business can begin to change the culture and system in Nigeria by refusing to engage in corrupt business activities, empowering its employees to do business ethically, and working collectively to strengthen institutions and laws that reduce corruption in the system and level the playing field for all business.

Ryan Musser is a Program Officer for Africa at CIPE.

Published Date: February 14, 2019