This blog is Part 1 of a two-part series on youth entrepreneurship in Korea.

South Korea is suffering from its highest rates of youth unemployment since the Korean economic crisis in 1998 . The youth unemployment rate, which calculates the number of unemployed 15-24 year olds, has steadily increased from 7% in 2002 to 9.5% in 2018, roughly totaling 408,000 unemployed youths. This 2.3% increase stands in stark contrast to the United States which shares similar GDP growth rate with Korea , but still managed to decrease youth unemployment rate by 5.8% over 5 years. Similarly, the OECD average youth unemployment rate is predicted to fall from 16.62% in 2008 to 11.09% in 2020. While United States and other OECD countries have been improving youth unemployment rates since the economic depression in 2008, the Korean situation has gotten worse.

Youth entrepreneurship may be an important tool to solve the country’s unemployment problems. According to the OECD, countries with a vibrant entrepreneurship environment show higher productivity rates, increased economic growth, and more robust job creation. However, Korean society is not open to youth entrepreneurship compared to other countries. The Global Entrepreneurship Monitor ranks Korea as 37th among 47 countries that have a social perception of “entrepreneurship as a good career”. This means that Korea ranks below neighbors like Taiwan (13), China (29), Indonesia (11), and India (23) regarding societal values of entrepreneurship. Korea’s Ministry of Education’s survey reports that 43.6% of university students want to work for the public sector and 37.8% want to be in the private sector. In contrast, only 3.3% of them want to be entrepreneurs. Starting a business was the least preferred future.

According to an OECD report, Korea has a 24.4% rate of necessity-driven entrepreneurial activities in 2015. This is one of the highest rates among OECD countries. Necessity-driven entrepreneurial activities are from people who do business because there are no other options. Improvement-driven opportunity entrepreneurial activities are from those who want to be independent and increase one’s income through business. Koreans have tendency to start business out of necessity compared to other OECD countries.

In 2017, newly elected President Moon Jae-in declared that Korean government would invest $700 million USD in 2018 to fund young entrepreneurs. This included hosting business model competitions and creating funds such as the “Youth Entrepreneur Fund” and “Innovation Challenge Fund” for youths. Back in Korea, I was in the leadership team of a student group called Social Enterprise Network that wanted to gain support from this new government policy. It was made up of a coalition of students from nine universities in Seoul with the purpose of encouraging social entrepreneurship amongst college students. Right after 2017 election, student society was vibrant with the support of government programs.

My student group joined three business incubators/competitions: a government agency, a social venture, and the board members of a Social Enterprise Organization. Our team’s idea was to create an application for migrant workers to get more access to information in Korea. After interviewing Vietnamese migrant workers and collaborating with a migrant workers’ rights activist, we figured out what information migrant workers may need to settle safely in Korea. Our mobile application had information on lawsuit cases, housing and insurance. The app was also planned to serve as a platform where migrant workers can gather online to post useful information. We succeeded in getting financial support from all the programs we attended. However, despite the financial support and mentoring, we could not make our ideas into reality in the end. Although I could hear from teammates who used the experience to get into a big multinational company in Korea, there was not a single member who became an entrepreneur or engaged in entrepreneurial activities later.

Our team succeeded in getting the funds but failed in making our idea into real business. Why weren’t we motivated enough to start a real business? To answer the question and hear what other students think of current government policy, I conducted a survey with students who participated in business model competitions in Korea. Out of 151 students surveyed, 30 students answered.

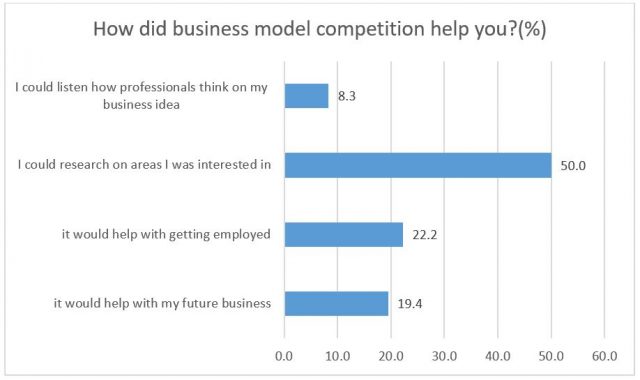

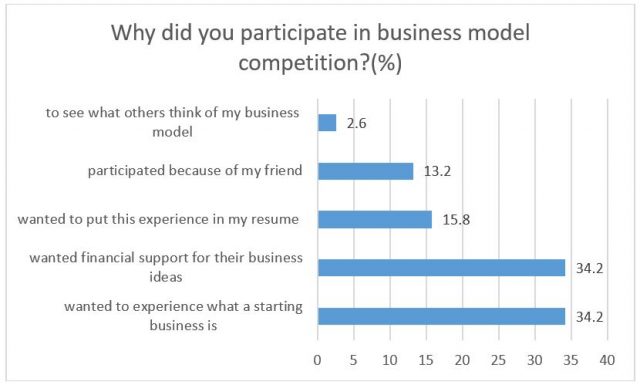

The key takeaway from the survey was the following; while students were overall satisfied with participating in business model competition, there were some problems with how the programs were delivered. The average satisfaction level was 3.88 out of 5, with 5 as the most satisfactory and 1 as least satisfactory. Students were largely satisfied with research experience they did while preparing for the competition. However, there were less students who replied that these programs were helpful because they could experience what starting up a business is like. This indicates that compared to participants’ expectation related to experiencing entrepreneurial activities, their takeaway was limited to indirect research.

Some of respondents also pointed out that there are too many programs compared to the number needed.

“Because the government is spending too much on business model competitions and funding [opportunities], there are students who just want the financial support and do not want to continue their business after the support ends. I think the government money is more than what people really need, and that you can easily find the source of finance if you try to get it.” – (2017) President of Social Enterprise Network.

After studying the result, I found that there are some questions regarding current entrepreneurship policy that should be addressed – what are weaknesses of government-led programs? Why are Korean youths still hesitant to become entrepreneurs despite all these efforts?

The next blog will look into Korean entrepreneurship ecosystem to find out problems lying behind this survey with possible solutions to enhance the ecosystem as well as controlling youth unemployment.

Lee Haein is a CIPE Asia Intern and a Asan Academy Fellow.

Published Date: May 23, 2019