Informality poses unique challenges to democracy and development practitioners. The informal sector, those working and living outside of the legally regulated, licensed, and incorporated private sector, can be inefficient, less productive, and ungovernable.

Practitioners must pay attention to these challenges to ameliorate marginalization and enhance representation. The economic, political, and social arrangements in a country might also create barriers to formalization, incentivizing informality. Even so, businesses and vendors in the informal sector are motivated to find innovative and often collaborative solutions to their problems. For example, in a previous article on informality, we explore the informal sector’s challenges during COVID-19 and highlighted how informal vendor associations organized, leveraging collective action to bargain and secure necessary aid and supplies.

This article investigates the intersection of space (location and access to services and opportunities) and incentives (the factors shaping decision making). This intersection highlights the informal sector’s independence and ingenuity as it fills gaps created by the lack of access to infrastructure and services. While the informal sector finds its own solutions, these solutions come with their own costs. As a result, it is better to view informality as something more dynamic than a simple problem in need of a solution. According to a recent ILO report, roughly 60% of the world’s employed population operates informally. We should look at the relationship between space and incentives to gain actionable insight into their challenges and opportunities.

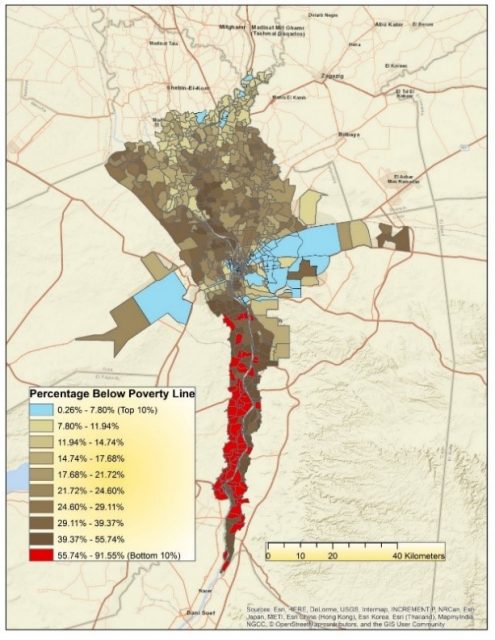

Spatial analysis is a useful tool because it explains how location and someone’s surroundings can impact access to services as well as influence opportunities. Egypt is an excellent example of this intersection. Cairo, for example, has severe spatial inequality, all the way down to the neighborhood level. Tadamun, a research initiative examining the built environment and local politics throughout MENA, produced maps specifying concentrations of poverty and wealth throughout Cairo. The first map (Figure 1) shows the spatial distribution of poverty measured as the percentage of residents below the poverty line.

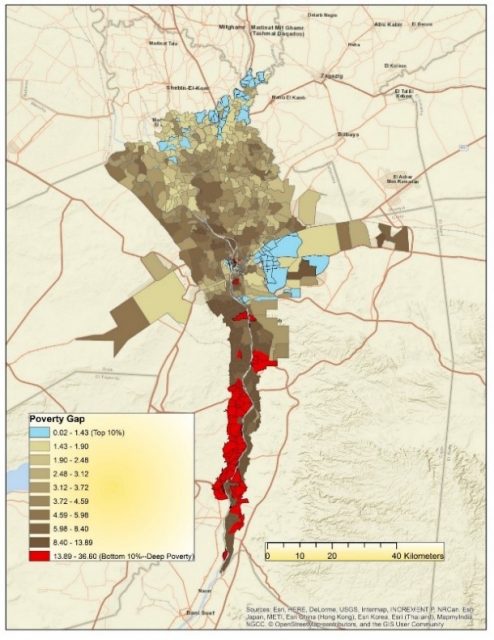

Meanwhile the second map (Figure 2) demonstrates the spatial distribution of the depth of poverty as measured by the poverty gap.

Both maps demonstrate that poverty is highly concentrated in specific areas rather than distributed randomly or evenly. For those living in the poorer areas and traveling to work in the city, “life is expensive.” Aljazeera’s article, Egypt’s Women Street Sellers, highlights the distances some women must travel from the urban periphery to the city center in order to earn money. One quote that stands out is from Aida Muhammad, who sells vegetables in Cairo during the day but must travel home to the outskirts in the afternoon to look after her children. For Muhammad, “life is expensive” because she must reach work early enough to secure a prime selling location away from formal businesses, which contest informal vendors that sell too close to their businesses, and secure transportation for the afternoon while missing out on additional selling time. Constantly moving incurs opportunity costs because selling time is lost, as well as material costs, because transportation can be expensive and in Muhammad’s case, frequent.

Egypt’s Women Street Sellers also highlights how negotiating and securing travel from poor, often informal habitats called ashwa’yat, can be an unreliable, dangerous, and expensive process in time, labor, and cost. Poor informal areas away from urban centers tend to lack public services, especially transportation, that those living and working in the formal sector use more frequently.

Since these communities lack access to public transportation, informal entrepreneurs fill the service gap and are incentivized to offer transportation via their motorcycles, rickshaws, cars, minibuses and microbuses and can do so at inelastic prices. Informal transportation demonstrates the informal sector’s agency and capacity to innovate and form their own networks of goods and services outside of the formal sector. The microbus network offers an autonomous transportation option outside of the limited and centrally located public transportation system.

Informal driver networks present both benefits and burdens to those relying on them for transportation. Drivers are one of the only sources of transportation for those traveling to work in the city center and for those looking for locations to sell. Individuals can access the informal driver networks at set and commonly known locations. However, if travelers live farther away, they must take a tuk-tuk or another vehicle to then find a ride on a larger vehicle going into the city center. Since Egypt gained access to Uber in 2014, some 40,000 drivers and more than one million riders have joined. However, Uber and other formal ride sharing services often have barriers to entry that block many informal drivers. Barriers include safety or car quality requirements, licenses, and other permits. Often, spatial inequality makes it more difficult to meet these standards if the relevant offices are located far away from informal areas.

The informal microbus network provides employment outside of a bureaucratic public-sector and the frequently undermined formal private sector. On the other hand, informal transportation can be very dangerous, unreliable, and over-reliance leads to severe traffic congestion, all of which complicate the precarity experienced by informal vendors.

Despite the drawbacks, informal transportation represents ingenuity in the informal sector and an economic, social, and political arrangement that makes it more difficult to participate in formal enterprises. This struggle highlights the opportunity to create pathways toward inclusive economic growth. In Egypt, the formal economy experiences barriers to registration, high taxes, unfair competition from military owned businesses, and a lack of transparency.

The current incentive structure is arranged to drive traders toward informality to avoid a skewed system that puts them at a disadvantage. For example, there is demand for transportation because of spatially concentrated inequality and the need for services in those areas. People come to their own solutions when given the chance—but there is work to be done to improve opportunities and to make it less expensive to conduct business.

Instead of conceptualizing informality as a problem to be solved, there is much more value in looking at the business and incentive ecosystem. Rather than ignoring underlying structures and trying to quickly force informal workers and traders into the formal economy, we should consider how the existing incentive structure pushes people into informality. In the case of Egypt, but also many countries with murky lines between the private and public sectors, forcing the informal sector into formalization causes more problems than it solves.

To this end, CIPE produced a roadmap called Transitioning to Formality, A Handbook for Policy Makers and Business Enterprises, contextualized for Egypt, that highlights important steps to ease processes in a way that will shift the underlying incentive structures. While the CIPE roadmap provides a longer and more detailed series of steps for a comprehensive and gradual formalization processes, the roadmap also provides several excellent suggestions that mitigate the impact of spatial inequality on informality:

- Easing licensing regulations and improving access. Acquiring a business license means that enterprises can make secure and reliable financial transactions, access reliable supply chains, and petition the government for services. However, offices that process these licensing requests are often located remotely, closed except at inconvenient times, and there is a great deal of redundancy, adding additional time, energy, labor, and financial costs.

- Better provision of utility services. In the CIPE study informing this roadmap, respondents cited the high cost and inaccessibility of basic utilities. Although the informal sector independently solves many of its own problems, these solutions create new problems as well. The public sector can empower non-state businesses by subsidizing rents that quickly become unreasonable, lowering penalties for late fees, and lowering the cost of service utilization. Many small enterprises operate far from where these services are based. Consequently, services essential to operating an enterprise can be difficult to secure or untenable in the long run.

- Land use allocation. Corrupt practices in land use allocation make it harder for informal enterprises to secure places to sell and bring goods and services to market. In the Aljazeera article mentioned above, one interviewee mentioned having to relocate several times a day because competition chased her away. Formal business owners often have connections to the military or the government. Selling spots may be subject to elite capture, an issue prevalent in many countries and rooted in corruption and a lack of transparency. Making this process transparent and fair places less stress on informal traders to secure transportation and selling locations, removing a considerable source of precarity from their lives.

For informal traders, secure selling sites, access to utilities and services, and obfuscated and redundant licensing processes and departments are difficult to deal with. It would be to the benefit of each stakeholder if an eye for location and place was included in plans to help the informal sector. Spatial inequality amplifies challenges experienced in the informal sector, but the CIPE Roadmap provides several concrete and actionable policies that can ameliorate these underlying structures and empower informal businesses and vendors.

Published Date: August 27, 2020